Language Is Africa’s Quietest Creative Inequality

Africa’s creative economy is often framed as a story of momentum. Afrobeats topping global charts. African films premiering at Cannes. Fashion weeks pulling international buyers into Lagos, Dakar, Accra, and Nairobi. On the surface, it looks like a continent finally being heard.

But underneath that growth sits a quieter, less discussed truth: language still determines who travels faster, who earns more, and who gets understood globally.

Not talent. Not originality. Not cultural depth.

Language.

The inequality no one wants to name

In most global creative markets, language is infrastructure. It determines discoverability, monetisation, media coverage, touring routes, and algorithmic reach.

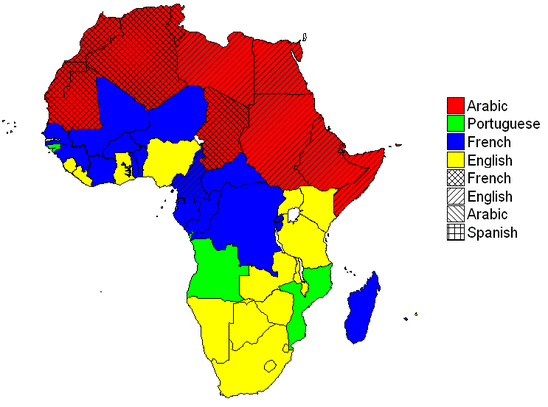

In Africa, this infrastructure is uneven by design.

English and Spanish dominate global music, film, publishing, and digital platforms. French, Arabic, Portuguese, and indigenous African languages operate at a structural disadvantage, not because they lack audiences, but because the systems that move culture across borders are not built for them.

This is why Anglophone African artistes often break out earlier. Why their work circulates faster. Why their stories are more easily framed by global media. And why Francophone, Lusophone, and Arabic-speaking creatives are frequently described as “regional” long after they have built serious cultural capital.

The gap is not visibility alone. It is economic velocity.

Language as an economic filter

Global platforms do not explicitly penalise non-English creators. But their systems quietly prioritise what is easiest to categorise, promote, subtitle, market, and monetise at scale.

Streaming platforms rely heavily on metadata, editorial playlists, and algorithmic signals trained on dominant language markets. Music in English travels across playlists more easily. Lyrics are quoted, translated, reviewed, and circulated faster. Press coverage multiplies.

For creators working primarily in French, Arabic, or local African languages, the friction is higher at every stage: slower global playlist pickup, less international press interpretation, reduced emotional access for non-native listeners, lower sync and licensing opportunities, and narrower touring circuits.

None of this reflects quality. It reflects legibility.

As Congolese-born French R&B singer Singuilar recently put it, rhythm can cross borders, but meaning often cannot. When your work depends on storytelling, vulnerability, or lyrical nuance, language becomes the gatekeeper to emotional connection and commercial expansion.

Why “just make it universal” is not a solution

The usual response to this problem is advice masquerading as strategy: sing in English, simplify lyrics, lean into dance records, or dilute cultural specificity.

That advice misunderstands the role of language in creative identity.

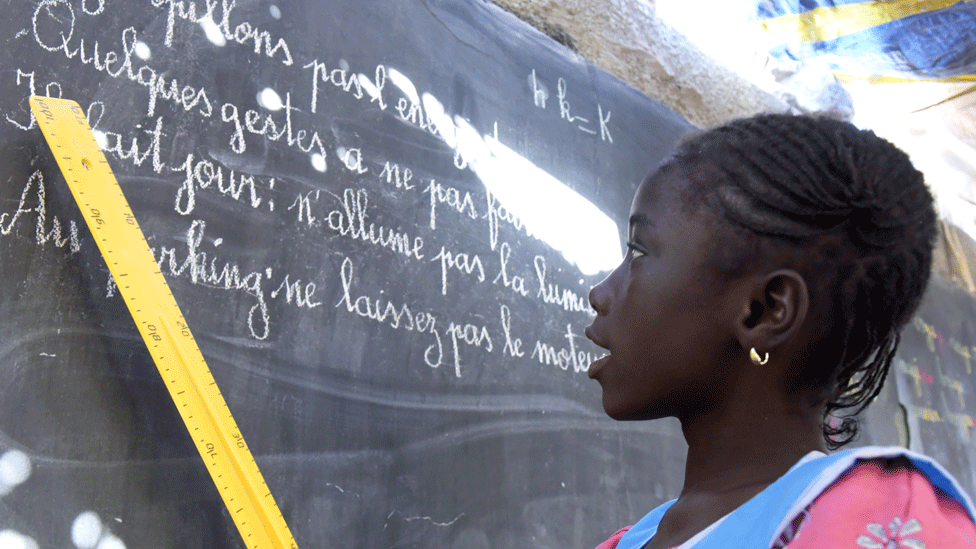

Language is not just a communication tool. It carries humour, history, rhythm, political context, and emotional weight. Asking creators to abandon their linguistic roots for global access often strips the work of what made it distinctive in the first place.

More importantly, it shifts the burden of adaptation entirely onto the creator, rather than questioning why global creative infrastructure remains linguistically narrow.

If Africa’s creative economy is truly globalising, then translation, localisation, and cross-cultural mediation should be part of the system, not an afterthought.

The uneven map of African cultural exports

Look closely at how African creativity travels, and the pattern becomes clear.

Anglophone markets dominate global narratives not because they produce more culture, but because their output is easier to integrate into existing global circuits.

Francophone Africa has produced globally influential sounds, fashion movements, and cinematic traditions for decades. Yet these movements often remain siloed within regional or diasporic ecosystems.

Lusophone African creativity is even more marginalised, despite deep musical and literary traditions that influence genres far beyond their borders.

Arabic-speaking African artists navigate an additional layer of complexity, caught between African, Middle Eastern, and European cultural markets without full ownership in any of them.

This is not a coincidence. It is the result of colonial language legacies colliding with modern platform economics.

Platforms scale content, not context

Digital platforms excel at scale. They are far less capable of carrying context.

Algorithms can detect engagement, but they struggle with cultural translation. They amplify what already fits existing patterns. As a result, content that aligns with dominant linguistic and stylistic norms benefits disproportionately from platform growth.

This is why certain African genres become globally visible only after being reframed, simplified, or translated by external markets. The culture travels, but the original creators often arrive late to the value chain.

The result is a creative economy where African influence is global, but African ownership remains uneven.

Language, power, and who gets paid

The real cost of language inequality is not aesthetic. It is financial.

Access to international publishing deals, sync licensing, touring circuits, brand partnerships, and cross-border funding is closely tied to how easily a creator’s work can be understood and marketed.

This is why English-speaking African creatives are more likely to secure international management earlier. Why their contracts scale faster. Why their work enters global revenue systems with fewer translation layers eating into margins.

For others, monetisation remains local or regional, even when cultural impact is continental.

In economic terms, language acts as a multiplier or a bottleneck.

What Africa is missing is not talent, but translation infrastructure

The solution is not to homogenise African creativity. It is to build systems that respect linguistic diversity while enabling global movement.

This includes professional translation and subtitling pipelines for music, film, and publishing; better metadata standards that support multilingual discovery; cross-border media platforms that contextualise African work for global audiences; investment in cultural interpreters, editors, and curators, not just creators; and policy frameworks that recognise language as part of creative infrastructure.

Other regions have done this deliberately. Latin music did not globalise by abandoning Spanish. It globalised by investing in translation, crossover marketing, and industry infrastructure that allowed Spanish-language music to scale without losing its core identity.

Africa has not yet made that investment at scale.

Why this matters now

Africa’s creative economy is entering a critical phase. Governments are drafting creative economy policies. Platforms are investing selectively. Global audiences are paying attention.

If language inequality is not addressed at the structural level, the next phase of growth will deepen existing gaps rather than close them.

Some creators will scale globally. Others will remain culturally influential but economically constrained. And the continent will continue exporting culture without fully capturing value.

The quiet inequality we can no longer ignore

Language rarely shows up in funding conversations. It is absent from most creative economy strategies. Yet it shapes outcomes more consistently than almost any other factor.

Africa does not lack creativity. It does not lack stories. It does not lack global relevance.

What it lacks is a system that allows its many languages to travel with equal power.

Until that changes, language will remain Africa’s quietest creative inequality, shaping who gets heard, who gets paid, and who is left translating themselves long after the world has moved on.

A guest post by

A curious mind exploring the crossroads of creativity and insight.