Can National Dress Days Actually Stimulate a Creative Economy

Last week, a garment caused a diplomatic ripple.

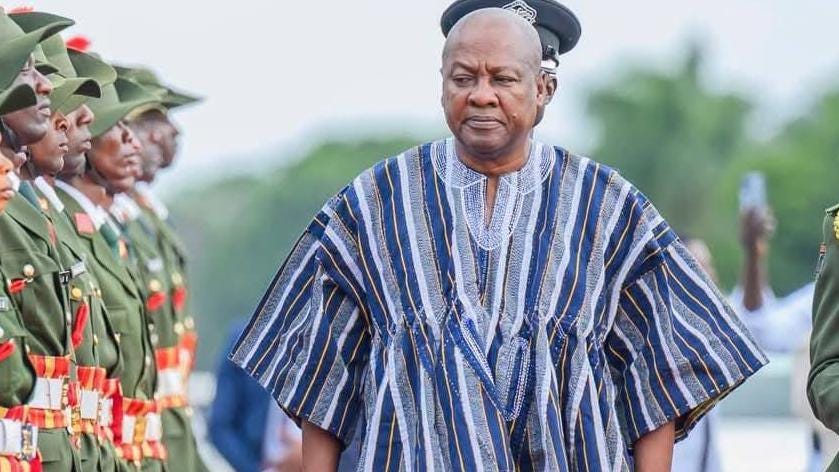

President John Dramani Mahama wore fugu - a handwoven smock originating from northern Ghana - during a February 2026 state visit to Zambia. Some online commentators mocked it as a “blouse.” The response was swift and digital. Ghanaian MPs posted photos of themselves in fugu. Fashion designers flooded social media timelines with images and production details. The diaspora joined from London, New York, and Toronto. What started as banter turned into a coordinated digital assertion of cultural pride that dominated African social media for days.

Then the government did something unexpected.

It formalized the moment.

Every Wednesday is now Fugu Day across Ghana’s public sector.

The state has taken a viral cultural defense and turned it into recurring policy. That shift is bigger than fashion. It forces a serious question: can national dress days actually stimulate a creative economy, or are they mostly narrative exercises that create pride without producing industrial transformation?

The Politics of Cloth

This is not the first time clothing has been weaponized for meaning in Ghana.

Kwame Nkrumah wore traditional kente and northern smocks deliberately at independence in 1957. It was not aesthetic nostalgia. It was visual sovereignty. It rejected colonial codes that had dictated what leaders wore for a century. It announced a new national identity on the world stage.

The same pattern repeated across post-colonial Africa:

Julius Nyerere’s safari suits in Tanzania

Kenneth Kaunda’s kaunda suits in Zambia

Mobutu Sese Seko’s abacost in Zaire

Clothing became shorthand for autonomy.

Mahama wearing fugu at the United Nations General Assembly echoed that lineage. It was a statement that Ghana would show up globally on its own terms, not in Western business attire. When Zambia’s President Hakainde Hichilema publicly announced he would order fugus in bulk from Ghana, symbolism crossed into potential trade. The garment moved from culture to commerce in real time.

Ghana’s Tourism Minister Abla Dzifa Gomashie declared that Fugu Day would “generate far-reaching social and economic benefits” for local weavers, designers, artisans and traders. The government hopes the initiative will “strengthen national unity, stimulate the creative economy, and serve as a powerful symbol of Ghana’s cultural confidence.”

But history shows that symbolism alone does not industrialize a sector.

Nigeria: Visibility Without Industrial Backbone

Nigeria has perfected what could be called Ankara diplomacy.

Its leaders wear prints abroad. Nollywood exports style to 100 million viewers across Africa. Afrobeats globalizes aesthetic codes - Burna Boy and Wizkid perform in elaborate Nigerian prints that become fashion references. Ankara dominates diaspora weddings from London to Houston, with the global African print fabric market estimated at $4 billion annually.

Yet Nigeria’s textile manufacturing base continues to struggle.

The numbers from 2024-2025 tell a stark story:

Textile imports surged 298% from 2020 to 2024, reaching ₦726 billion ($726 million)

The sector’s GDP contribution dropped to 1.63% in 2024, down from 2.02% in 2019

Nearly 90% of textile products consumed in Nigeria - worth over $4 billion annually - are imported

The industry that once employed 350,000 workers in the 1980s now employs fewer than 25,000

In 2024, Nigeria’s textile exports totaled just $47.4 million, while textile imports hit $726 million. The value chain ruptures at every point. A dress might be designed in Lagos, printed in Guangzhou, shipped to London, and sold to a Nigerian diaspora customer - yet Nigeria captures minimal economic value beyond the design fee.

The culture exports. The industrial capacity lags. Visibility did not automatically rebuild the factories. That is the warning.

India: When Symbolism Meets Structure

India offers a sharper contrast.

Under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Khadi - the handspun, handwoven cloth that symbolized Gandhi’s independence movement - was repositioned as both nationalist fabric and economic instrument. Public officials promoted it. Campaigns encouraged citizens to buy it during national holidays. But crucially, the state backed it with infrastructure.

The results from 2024-2025 are measurable and dramatic:

Sales reached ₹1.70 lakh crore ($20 billion) in FY 2024-25, up 447% from 2013-14

Khadi garment sales alone jumped 561%, from ₹1,081 crore to ₹7,145 crore

Production increased 347% over the same period

Employment grew 49.23%, creating 1.94 crore (19.4 million) jobs

Artisan wages increased 275% over 11 years, with a 20% hike announced for April 2025

The Khadi and Village Industries Commission received consistent budget increases and infrastructure support. Cooperatives accessed working capital loans. Retail channels expanded from 8,000 outlets in 2014 to over 9,000 by 2023. Branding professionalized - Khadi appeared in urban malls, e-commerce platforms, and airport boutiques.

Under the Pradhan Mantri Employment Generation Programme, over 1 million units were established, generating employment for over 9 million people.

The revival was not only about wearing Khadi. It was about financing Khadi, creating distribution networks, and integrating it into modern retail. That difference turned cloth into employment infrastructure.

Rwanda: Industrial Policy First, Aesthetics Second

Rwanda approached textiles less emotionally and more structurally.

The Made in Rwanda initiative, launched in 2015, restricted secondhand clothing imports through tariff increases - from $0.20 per kilogram to $2.50 per kilogram in 2016. The move faced international trade pressure, including suspension of duty-free apparel exports to the United States under AGOA. But the government held firm.

The results by 2024-2025 show measured progress:

Textile and leather output grew from Rwf34 billion in 2017 to Rwf154 billion by 2024

Rwanda’s apparel market reached $426.10 million in 2024

Local garment factories now supply 5% of domestic consumption, up from near-zero

The government projects reaching 100% domestic clothing production by 2029

The National Strategy for Transformation (2024-2029) targets creating 250,000 jobs annually, with textiles as a key sector

New investments continue. In 2024, a knitting and sewing mill was established in Muhanga Industrial Park capable of producing over 1 million garments annually at full capacity. The government secured priority procurement policies - school uniforms, police uniforms, and security force equipment must favor local manufacturers, potentially saving Rwf17-20 billion ($15-18 million) in import costs.

It was about reshaping supply chains from the start. The aesthetic narrative - Rwandan leaders wearing locally made suits and dresses - followed policy, not the other way around.

Where Fugu Stands

Ghana’s Fugu Day sits at a crossroads.

It has:

Viral momentum

Pan-African symbolism

Diplomatic interest from neighboring countries

Youth participation across social media

State endorsement from the highest levels of government

But momentum is not infrastructure.

Fugu production is largely artisanal. Traditional smocks are handwoven on narrow looms - typically 4 to 6 inches wide - in strips that are then hand-stitched together into the final garment. Weaving a complete fugu can take 3 to 5 days of skilled labor. Production centers exist in Bolgatanga, Wa, and surrounding northern regions, but output remains limited.

Ghana produces an estimated 15,000 to 25,000 traditional fugu garments annually through artisanal channels. Compare that to potential demand: if even 10% of Ghana’s estimated 300,000 public sector workers regularly purchase fugu for Wednesdays, that’s 30,000 customers seeking multiple garments per year.

Already, reports indicate fugu prices in Accra markets have increased 15-20% since the February 2026 announcement.

Scaling requires:

Organized weaving cooperatives with access to working capital

Cotton supply stabilization (Ghana’s domestic cotton production has declined over decades, requiring imports)

Export logistics support for regional orders

Quality certification to differentiate authentic Ghanaian fugu from imitations

Intellectual property protection to prevent design appropriation

If Wednesdays increase demand without expanding capacity, two things happen. Prices rise temporarily, or cheaper replicas flood the market. Machine-made imitations from China or India, lacking the cultural authenticity and labor intensity, could undercut artisans. Neither outcome builds a sustainable textile economy.

Industry voices already recognize the risk. Gabriel Agambilla, a textile advocate, urged President Mahama to “implement measures that safeguard and promote local production of the fabric” and warned against allowing foreigners to exploit the surge while local producers lose out.

Exporting Identity Is Easy. Retaining Value Is Hard.

There is a powerful opportunity here.

If fugu becomes normalized as formal Pan-African attire at African Union summits, ECOWAS meetings, diplomatic visits, and diaspora cultural events, Ghana could position itself as the origin point of a continental uniform. That is soft power with commercial implications.

But soft power without supply chains is theatre.

If regional demand increases faster than Ghana’s weaving clusters can scale, production will migrate. Industrial manufacturers outside Ghana - already skilled at appropriating African aesthetic codes - will replicate the design using mechanized processes at lower costs. Value will leak. The garment will trend globally. The margins will travel to factories in Asia or North Africa.

This pattern is already visible. After kente cloth gained global recognition in the 1990s and 2000s - worn by celebrities, appearing in fashion magazines, featured in diaspora celebrations - Chinese manufacturers began producing machine-made kente-style fabric. The aesthetic spread, but Ghanaian weavers captured a shrinking share of global kente-related revenue.

The GDP Question

Can national dress days move GDP?

Yes. But only under certain conditions.

Demand must be sustained, not seasonal. If fugu remains a Wednesday phenomenon without cultural embedding beyond government offices, demand will plateau.

Producers must access financing to scale - microfinance for weavers, small business loans for cooperatives, venture funding for modernized production facilities.

Artisans must formalize into bankable entities with legal structures, tax compliance, and credit histories that enable institutional lending.

Export frameworks must support cross-border trade under AfCFTA (African Continental Free Trade Area). Currently, intra-African textile trade faces bureaucratic barriers that can delay shipments for weeks.

Data must track employment growth, production volumes, and export earnings. Without measurement, the initiative becomes untraceable in national accounts. Ghana’s statistical agencies should establish baseline metrics:

Number of weavers

Average production per artisan

Domestic sales versus exports

Price trends

They should publish quarterly updates.

Otherwise, dress days become morale campaigns. They create unity. They project pride. They generate headlines and social media engagement. But they do not restructure economies or appear meaningfully in GDP growth figures.

The Real Test

The online argument is already won.

Ghanaians reclaimed the narrative. Fugu dominated African Twitter and Instagram. The state amplified the momentum with official policy. International media covered the story. Even Ghana’s Education Minister proposed extending the concept to schools with a nationwide cultural dress day. The symbolic victory is complete.

Now comes the part that determines whether this is a cultural footnote or an economic pivot.

If Fugu Day becomes the entry point into a serious textile development strategy - with dedicated funding, cooperative organization, supply chain investment, quality assurance mechanisms, and export promotion - it could mark the early stages of structured creative industry growth. Ghana’s Ministry of Trade should coordinate with the Ministry of Tourism, Arts and Culture to develop a five-year fugu sector plan with measurable targets.

If it remains a weekly aesthetic ritual without corresponding investment in production infrastructure, it will settle into symbolic comfort. Government workers will wear fugu on Wednesdays. Social media will celebrate. Cultural pride will be reinforced. But weaving cooperatives in Bolgatanga will still struggle to access working capital, and Chinese manufacturers will still produce the bulk of African-print fabric consumed across the continent.

Cloth can carry history. It can carry pride. It can even carry diplomacy.

The question is whether it can carry capital - whether it can generate employment, increase export earnings, formalize artisan clusters, and contribute measurably to GDP.

That depends not on Wednesday. It depends on what the state builds around it.

A guest post by

A curious mind exploring the crossroads of creativity and insight.